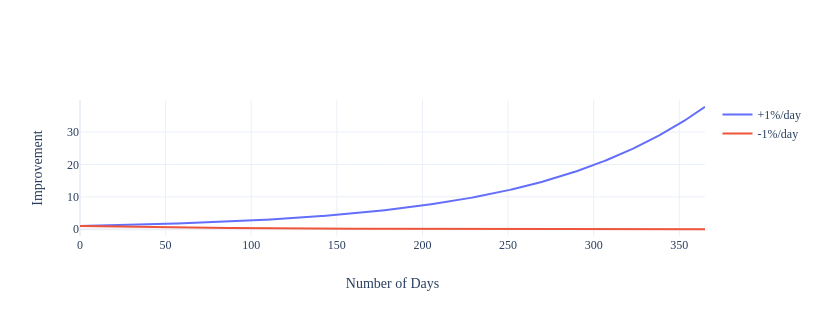

If you have heard of lean production, kaizen or read anything of James Clear, you might have come across a graph something like the following.

Marginal gains and marginal losses over 365 days

Marginal gains and marginal losses over 365 days

This is a figure showing the power of marginal gains. The idea is, in essence, that getting 1% better everyday at something compounds to give you astonishing improvements.

I have a problem with this.

Before we ponder, let us discard the fact that daily/circadian habits may be easier to implement for most people. And let us also ignore fatigue, for the sake of fictive calculation here.

Let’s say you are practicing a new instrument, the tuba. Every hour you put in it yields 1% of improvement. Then, if you practice everyday, in a year or 365 days, you get about 37.78x better.

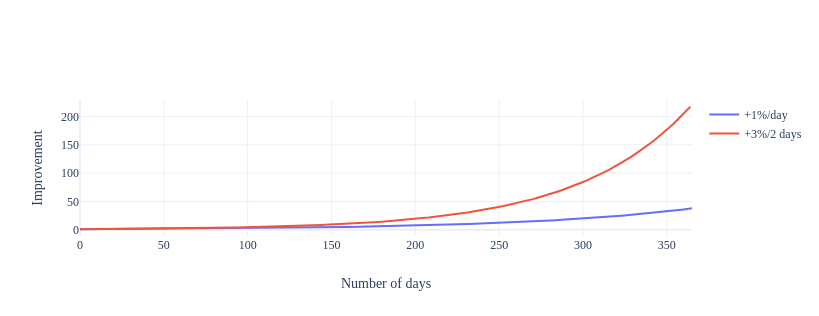

But you’re a busy, busy person. It’s just as easy for you to practice for a 3-hour session once every 2 days than allocate an hour everyday. So, if you practice every other day in this way, in a year or after 182 sessions, you get about 216.96x better.

Marginal and non-marginal gains over 365 days

Marginal and non-marginal gains over 365 days

Wait, what?

Small steps vs Batching

As many point out, continuous improvement is not a small step, even though it consists of small steps. A daily habit is like a subscription service, every day, it takes a bit out of your total time wallet. Paying 100 bucks a weekend is nothing, but you balk at paying 10 bucks every day. And rightly so.

Popular culture is full of grandiose gestures and strenuous training montages, and we have been instilled this idea that giant leaps are the way forward. They are exciting, and you feel like you’re getting somewhere. Copywriters everywhere love the term ‘quantum leap’. This one purchase, this one article, this one person will change you forever, everyone’s shouting. These are all short-term feel-good psychological tricks.

But that does not mean taking small steps more frequently is the end-all. Take batching, for example. This is a practice we use frequently, often unconsciously. It reduces the friction of gearing up, physically and mentally. A common example is clearing your inbox, generally better batched for a short burst than spread throughout the day like a camel task. Or if you have ever been on a sprint, you know what I’m talking about. Sometimes, taking leaps is better.

So we can see a sort of divide, although not a dichotomy, between steps and leaps (no quoting Armstrong here).

| Small steps |

|

| Daily habits |

|

| Lean manufacturing |

|

| Revolutions |

|

| Experience |

|

Okay, so we seem to have two profiles, but when is which useful?

There’s a hidden variable at play here that we haven’t talked about.

Uncertainty and the risk of marching down the wrong road

If you have taken music lessons, you might have noticed that most instructors put emphasis not on relentless speed and improvement, but on avoiding bad habits. The same in fitness. It’s okay if you cannot bench your target weight, but bad form is a big no-no. To get fast at typing, the first thing you need to perfect is your accuracy.

Let’s return to the graph.

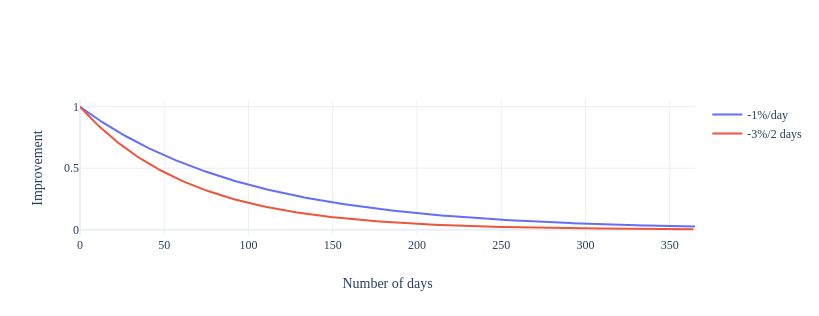

Say, instead of improving every day, you’re getting worse. If you get 1% worse every day for 365 days, you end up about 0.03x your original prowess. Which seems bad, until you realize what our 3-hour session every other day will look like when it causes deterioration. If you get 3% worse every 2 days 182 times, you end up around 0.004x where you started. You’d want to avoid that, right?

Marginal and non-marginal losses over 365 days

Marginal and non-marginal losses over 365 days

If you had a magic 8-ball that could tell you if your tuba skills have gotten better or worse by 1% - essentially providing a metric for evaluation, then the 2-day practice schedule would be worse. You would rather have marginal gains than maximal losses, in this scenario.

And here’s where the divide between steps and leaps comes into play. In some domains and tasks, there is little uncertainty. You can see if your laundry is folded or not. You are not in doubt whether you’ve progressed in clearing your inbox or regressed. In other domains, however, gauging progress is not so easy. Take learning most skills, for example. Or trying to test out a business plan. You cannot trust your results in these cases, as they could be flukes.

Tread carefully in murky waters - this is a banal advice. But to practice it effectively is not so easy.

Suprisingly wise biker advice

When I was trying to improve my two-wheeler skills, I came across a saying on a biker forum. ‘Slow is smooth, smooth is fast’ has possibly military origins. What connects the military and motorcycles is the risk. One wrong move and you are injured, possibly dead. So you cannot afford to be jerky and uncoordinated.

This has become my go-to mantra after ‘This too shall pass’ and ‘I Ate’nt Dead’ for its gentle reminder of how to learn.

The paradox is this: deliberately slowing down can, and often does, lead to an increase in speed.

This is not an excuse for laziness or mediocrity, however. It is a focus on improving process over result, and having accuracy and form as your targets. In your journey to self-improvement and self-creation, strive for smoothness.

Key takeaways:

-

Two profiles for progress - small gains and large leaps.

-

If higher uncertainty, then higher chance of regress - prefer marginal gains in such cases.

-

Focus on smoothness/form/process over speed/gains/results by deliberately slowing down when necessary.